From the Financial Times this week, following a negative trading update from tobacco behemoth British American Tobacco: “BAT, which makes Dunhill and Lucky Strike cigarettes, said competition from illicitly sold disposable vapes and smokers switching to cheaper cigarette brands or quitting altogether had dragged down US combustible sales.”

Put more simply: “Damn it! We have competition.”

It teaches a couple of things:

- Brands, without advertising, which in the case of tobacco, is restricted or banned in most parts of the world, cannot stand out in a competitive global environment.

- No matter who you are, there is always someone more nimble, more creative, and often cheaper, ready to gnaw at your market share.

- If you produce a product that is addictive and damaging, it will ultimately be usurped either by growing public awareness, regulation or competitors seeking to win on price.

Those are lessons the fossil fuels industry (and the rest of us who consume its products daily) could learn from.

Imagine if there was a ban on fossil fuel advertising in the same way as there is on cigarettes? It’s a crazy thought, or maybe not. It would certainly provide more space for cleaner alternatives to stand out. The reality is that there are tens of thousands of smart people all over the world looking at alternative ways to clean up the planet, from capturing carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it in the ground, to new modes of generating power from renewable sources. And, a bit like tobacco, our economies are built on the back of fossil fuels and the prospect of weaning ourselves off them in a world that does not have sufficient alternatives, is terrifying.

At COP28 here in Dubai, the language is about “transition” and the acceptance that there is no benefit to humanity today putting an immediate hard-stop on their use, but unless we can produce lucrative alternatives, at scale and quickly, there will be no incentive to reverse current trends in production.

The science demonstrates the negative impact of carbon missions, chiefly from fossil fuels, yet those dependent on their production show little intent on dialling back on their exploitation and use.

When Anton Rupert established the BAT precursor Voorbrand in 1939 manufacturing snuff, and later cigarettes, he saw it as recession proof, and because of the addictive nature of the product, ensured he had repeat customers, many of whom would live to a ripe, if unhealthier, old age.

There was also little competition from other vices back then.

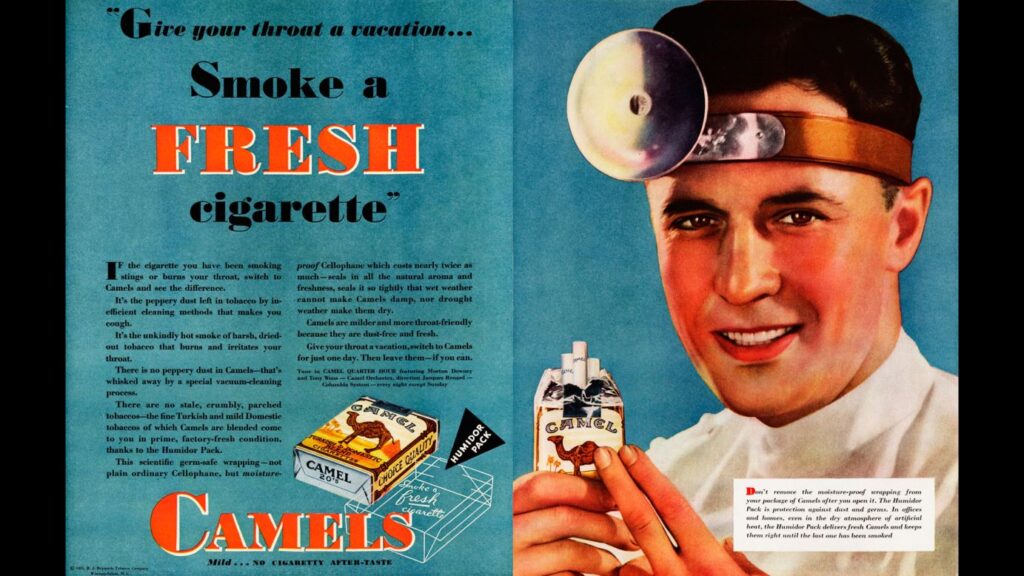

That, coupled with some of the most compelling advertising campaigns in history, led to a surge in global consumption of tobacco products for decades. There was even a period where some doctors were roped in to promote smoking.

(There is a great Chesterfield ad in which a doctor is quoted as saying he tells his patients to smoke Chesterfield.)

It took a while for the science to take hold and two generations of education, legislation and high taxes to see demand begin to wane.

It demonstrates that with the correct will and application, demand patterns can change. However, the problem with fossil fuels, is that the crisis needs to be tackled far more urgently as scientists warn that sort of incremental slow-burn approach will be disastrous for our descendants.

Regular COP attendees understand that making progress on mitigating climate change is fraught with complexity and know that the pace of globally agreed steps to mitigate the crisis are too slow. If governments made it tougher for oil majors to operate, as they have with cigarettes, and act quickly and decisively the world may stand a chance to slow the rate of damaging change.

However, as the arrival of Russian president Vladimir Putin in nearby Abu Dhabi and later in the day in Saudi Arabia demonstrated; there is still a significant appetite for the production and sale of fossil fuels, despite the fact that just up the road nearly 100 000 people have been slugging it out hoping to find a way to mitigate against a disaster which is already making its presence felt.